Books are to be call'd for, and supplied, on the assumption that the process of reading is not a half-sleep, but, in highest sense, an exercise, a gymnast's struggle; that the reader is to do something for himself, must be on the alert, must himself or herself construct indeed the poem, argument, history, metaphysical essay--the text furnishing the hints, the clue, the start or frame-work. Not the book needs so much to be the complete thing, but the reader of the book does.

- Walt Whitman, Democratic Vistas (1871)

Yes, this does read like an exhortation for an author like Joyce to bring forth books like Ulysses and Finnegans Wake. Whitman not only called for books "on the assumption that the process of reading is not a half-sleep" to wake a reader into a more fuller alertness, but to involve the reader in the construction of meaning in the work itself. In this way Whitman and Joyce seem to be in conversation, and Joyce did own a copy of Whitman's Democratic Vistas in his library. He was also inspired by Leaves of Grass ever since he was a young writer and he made references and allusions to Whitman repeatedly in his work, especially Finnegans Wake. That quote alone though, from a book Joyce owned, by an author he admired, could be an intriguing answer to the persistent question of why each of Joyce's books increasingly challenges the reader so much. It's worth thinking about, at least.

Lately, I've been interested in Walt Whitman (1819-1892) and what impact he had on James Joyce (1882-1941), and this influence seems more significant than most commentators have tended to note. This interest sprung from time I've spent in the past year around south Jersey and Philadelphia areas where so many places are named for Whitman, who spent the final two decades of his life at a house in New Jersey recovering from a stroke. While I was driving across the Walt Whitman Bridge to enter into Philly from Jersey one day, I recalled the first time I encountered the impressive harp-shaped Samuel Beckett Bridge in Dublin and how impossible it seemed that there might be a prominent bridge named after a poet in the USA. The naming of the New Jersey bridge in honor of Whitman happened in the mid-1950s and sparked the local conservative Catholic community into an uproar, one person offering this critique in a letter: "As a thinker Walt Whitman possesses the depth of a saucer and enjoys a vision which extends about as far as his eyelids. A naturalist, a pantheist, a freethinker, a man whose ideas were destructive of usual ethical codes- is this a name we wish to preserve for posterity?" The Port Authority decided to keep the name, and a statue of Whitman stands near the bridge this day. Whitman once wrote "The proof of a poet is that his country absorbs him as affectionately as he has absorbed it." Joyce was an exile from Ireland for nearly four decades, yet his books concentrate entirely on Ireland. The initial reception of Joyce's work in his native country, though, was far harsher than any reactionary furor against Whitman. Each country has since affectionately absorbed its poet, Joyce is now celebrated in his native Ireland, just as Whitman is revered in America. The two authors are also among the prime literary heroes celebrated across the entire globe. Finnegans Wake has been translated into Japanese and its translation into Chinese was advertised on billboards in Shanghai. I was struck recently while traveling in Asia when I passed a huge bright colorful billboard in Bangkok that featured this quote: "Peace is always beautiful" - Walt Whitman.

It's been interesting for me while reading Leaves of Grass alongside my ongoing reading of Finnegans Wake with different groups, and noticing how often there's a noticeable dialogue across eras between Whitman and Joyce. According to Stanislaus Joyce in My Brother's Keeper, James Joyce's interest in Whitman dates back at least to 1901. An early notebook Joyce wrote poems in around 1901-1902 was titled "Shine and Dark" the name derived from Whitman's line "Earth of shine and dark mottling the tide of the river" from "Song of Myself." This would've been when Joyce was just turning 20 years old and yet consider how the images in that one Whitman line resonate with the mytho-cosmic river of life Joyce wrote about decades later in Finnegans Wake. The dual "shine and dark" opposites dominate the fabric of the Wake like opposite riverbanks, "mottling the tide" of the river, darkened by earth/mud, like "our turfbrown mummy" (FW 194.22) Anna Livia (the tidal river Liffey)---it's all there in that one line from "Song of Myself." Another indication of how Joyce felt about Whitman's poetry during these early years of his writing is found in the essay Joyce wrote in 1902 on the Irish poet James Clarence Mangan where his effusive praise for the Irish poet is tempered with "it does not attain the quality of Whitman."

In the winter of 1906 after having left Ireland and settled in Rome, Italy, the 24-year-old Irishman Joyce was working as a clerk in a bank trying to support his wife and newborn child. Joyce was miserable with his life at that point, he hated Rome and he had barely any leisure time thanks to the grueling demands of his clerk job which involved working 8:30am to 7:30pm handwriting hundreds of letters per day. He worried about how he could ever find the time and energy to read or write anything. The poems of Whitman fed his soul around this time, we know because on December 7th, 1906, in a letter to Stanislaus, he mentions: "Thanks for Whitman's poems. What long flowing lines he writes." You can just imagine the young writer struggling at that stage of his life and how he may have been impacted reading lines like these from Whitman's poems:

"I dilate you with tremendous breath, I buoy you up"

"Let your soul stand cool and composed before a million universes.""Something long preparing and formless is arrived and form'd in you,

You are henceforth secure, whatever comes or goes."

(Whitman quotes are from the 1892 edition of Leaves of Grass which seems most likely the one Joyce possessed.)

Brian Fox's book James Joyce's America (2019) deals extensively with Joyce's view of Whitman. Fox shows how Whitman had gained great influence in the Irish literary world "since at least the 1870s" (Fox, 127). WB Yeats and John Eglinton (the real world Dublin librarian/author who appears as a character in Ulysses) were especially big enthusiasts of Whitman, but Fox argues the Irish republican nationalists "made him in their own idealized image" (Fox, 129) and in the process turned the radical poet into something conventional and orthodox. Fox tries to argue "that Joyce responds to this by turning Whitman against the orthodox ranks of his supporters" (Fox, 128), who Fox repeatedly refers to as Whitmaniacs. James Joyce's America is full of hot takes and fresh readings, and in discussing Whitman and Joyce, Fox builds an argument that Joyce initially viewed the American poet as a model decolonized national poet, but Joyce's placement of Whitman in Ulysses is more nuanced, and that "it would appear that the significance Whitman had for the younger Joyce as a potential model for a national poet did not translate into the later work, particularly Finnegans Wake." (Fox, 135) On this last part I disagree with Fox. Even he himself documents the extensive presence of Whitman in Ulysses and he notes some (but not all) of his appearances in the Wake.

Fox makes it seem like young Joyce was a huge fan of Whitman, he argues that in Ulysses he started to become more agnostic about the American poet, and then by the time of Finnegans Wake he has become practically hostile and mocking of Whitman. Reading this felt as if Fox wanted to fit Joyce's views on Whitman into something like the progressive structure of lyrical-epic-dramatic form (outlined in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man), whereby once he gets to Finnegans Wake, Joyce has become an indifferent god paring his fingernails. Doesn't it make more sense, considering all the references to Whitman in the Wake, that the poet he had loved and was inspired by as a youth remained an influence throughout his life? Giordano Bruno is one good example of a figure the young Joyce adopted as his hero and maintained an interest in while working on the Wake. There are other examples (Dante, Shakespeare, Ibsen). Why make Whitman out to be an aberration? It's clearly documented that Joyce had an appreciation for Whitman as early as 1901 all the way thru the 1930s. Give Whitman that props. None of this is to disparage Fox's superb study of the meaningful American connections in Joyce's life and career, but I disagree with his framing of the Whitman influence.

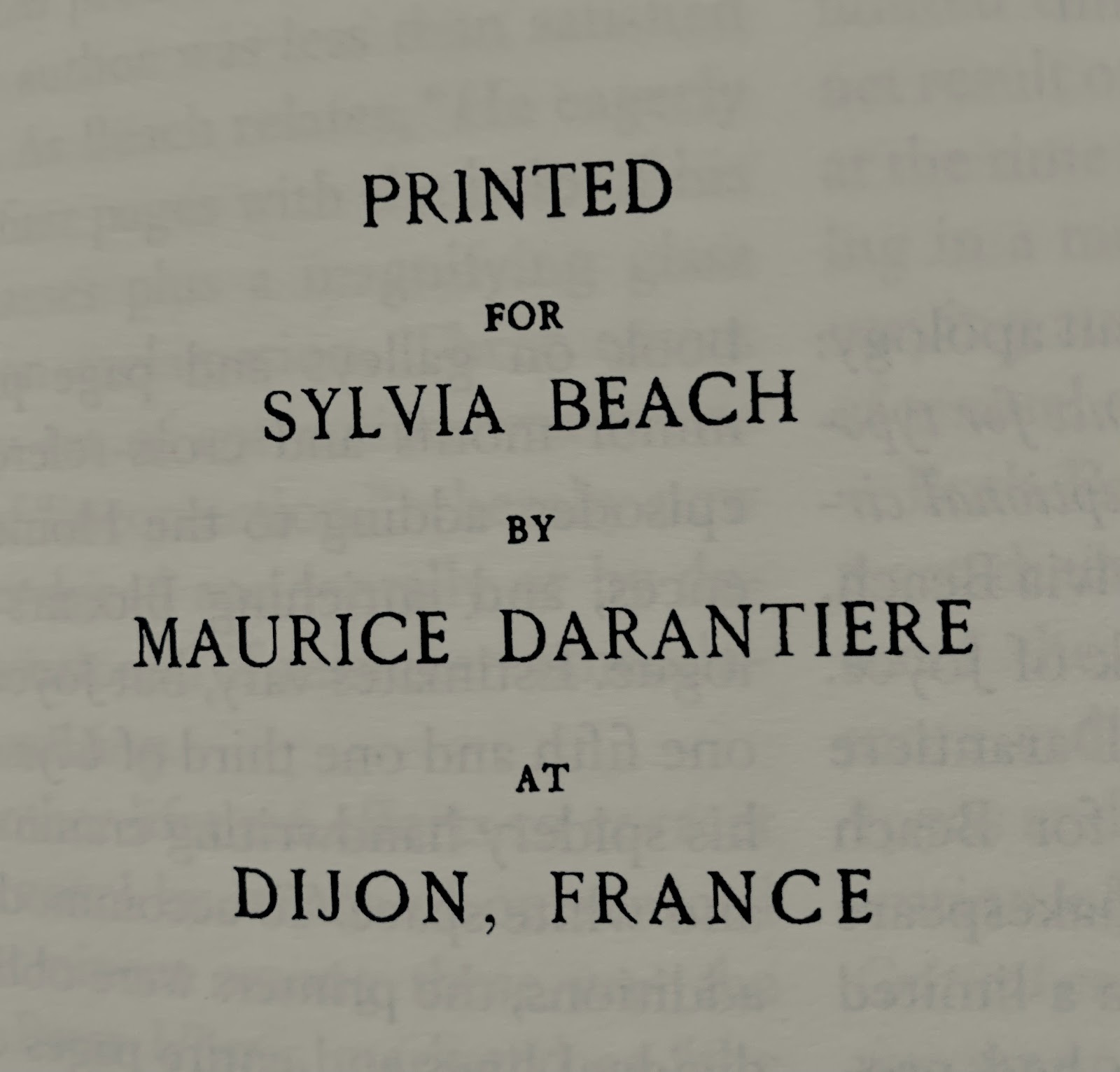

A good counterpoint to the assertion that Joyce no longer held Whitman in high esteem while working on the Wake comes from the story of when Sylvia Beach transformed Shakespeare & Co bookshop in Paris into a Whitman shrine one year. This was in 1926 when Joyce was fully immersed in crafting his Work in Progress that would become Finnegans Wake. Sylvia Beach was assisting Joyce with his manuscripts while also working on French translations of Whitman with Adrienne Monnier. That year, Sylvia Beach founded the Paris branch of the Walt Whitman Committee, to be headquartered at Shakespeare and Co. There's a whole chapter about this in the excellent book Sylvia Beach and the Lost Generation: A History of Literary Paris in the Twenties and Thirties (1983) by Noel Riley Fitch. A party in the bookshop that February is described: "At the party for Ulysses's fourth birthday (the forty-fourth for Joyce), at which both author and publisher wore eye-patches, they talked of Sylvia's plans for the Whitman exhibit, and Joyce quoted some lines from Whitman's poetry." (Fitch, 228) Later that year, the bookshop was decked out for a celebration of Whitman, attended by the likes of Joyce, Hemingway, Ezra Pound, and other Paris literati. Beach recalled of that event: "Only Joyce and the French and I were old-fashioned enough to get along with Whitman." (232) So, clearly Joyce maintained his admiration for the American poet during the period while he was writing the Wake.

******

The text of Finnegans Wake has a bunch of references to Whitman and Leaves of Grass. A quick rundown:

- FW 81.36 "the cradle rocking equally" etc alludes to Whitman's line "Out of the cradle endlessly rocking" from Leaves of Grass

- FW 263.09 "old Whiteman self" would be Whitman and his "Song of Myself" which Joyce alludes to most often. Reading thru the rest of this chapter you'll find lines that sound like Whitman, see for example 274.03 "The allriddle of it? That that is allruddy with us, ahead of schedule, which already is plan accomplished from and syne."

- FW 329.18 "The soul of everyelsesbody rolled into its olesoleself" captures the essence of the pancosmic perspective in "Song of Myself" where Whitman contains and embodies everything and everyone. This line in the Wake also describes the Here Comes Everybody character at the center of the book. HCE definitely comes across as a version of the self in Whitman who declares, "I am an acme of things accomplish'd, and I an encloser of things to be."

- FW 469.25 "this panromain apological which Watllwewhistlem sang" again refers to "Song of Myself" and its author "Watllwewhistlem" with the capitalized W making for a whimsical Wakean transformation of Whitman's name.

- Virtually the entire Yawn chapter (III.3) and especially the section known as Haveth Childers Everywhere (on pgs 535-554) bears considerable Whitman influence. Adaline Glasheen was the first to point this out in her Census of Finnegans Wake. J.S. Atherton confirms this in his Books at the Wake: "The similarities do in fact suggest that Joyce had Whitman's work in mind when he wrote these passages." (p. 288) Donald Theall in his Joyce's Techno-Poetics also discusses this at length. When HCE begins his monologue the text says "Old Whitehowth is speaking again" (FW 535.26). This section in Finnegans Wake is the rare moment when the central figure HCE speaks at length and it is here where Joyce most clearly links his everyman character HCE with Whitman.

- A general point of comparison between texts: Whitman, who worked as a printer and self published the first edition of Leaves of Grass in 1855, went pretty far off the rails with using exclamation points in Leaves. The final omnibus 1892 edition of 334 pages has by my count at least 2.2 exclamation points per page. Finnegans Wake is as exhortative as any book, the title can be read as an exhortation (finnegans, wake!) and it far exceeds Leaves with more than 5.4 exclamation points per page!

*****

"There is more wisdom in your body than in your deepest philosophy," wrote Nietzsche. This idea is prominent in both Leaves of Grass and Finnegans Wake. Each celebrates the biological body as a living artifact of all that came before it, a pinnacle of all that led to the production of this physical being, from the birth of the universe and the formation of cells and the earth to the development of living organisms and the survival of species through millennia. All of that is inside of us. The sleeping body at the heart of Finnegans Wake is known as Here Comes Everybody and his descent into the deepest primordial sleep comes across in a fabric made of more than 70 languages. ("Human bodies are words, myriads of words," Whitman wrote.) The concept of time melts into one single rippling pan-cosmic plane and somehow it seems the Wake contains all that ever was, is, or shall be. Yet on one level the main character of the book is a middle-aged pub owner asleep with his family in their house in Chapelizod, outside Dublin.

In Leaves of Grass, Whitman addresses you the reader directly, whoever you are, and celebrates your existence.

"Whoever you are! you are he or she for whom the earth is solid and liquid,

You are he or she for whom the sun and moon hang in the sky,

For none more than you are the present and the past,

For none more than you is immortality."

Even the tiniest most insignificant life forms are the source of infinite glories. "I believe a leaf of grass is no less than the journey work of the stars... And a mouse is miracle enough to stagger sextillions of infidels," Whitman wrote. There are many passages in Leaves of Grass which resonate with what Joyce was trying to do with the Wake. And whereas the Wake's language is obscure, dense, difficult to comprehend---and we've already touched on the influence Whitman might've had on those linguistic pyrotechnics---when you notice how often Joyce alludes to Leaves of Grass you might begin to read and interpret Leaves of Grass as a guide to Finnegans Wake, in less opaque language.

"Immense have been the preparations for me,

Faithful and friendly the arms that have help’d me.Cycles ferried my cradle, rowing and rowing like cheerful boatmen,

For room to me stars kept aside in their own rings,

They sent influences to look after what was to hold me.

Before I was born out of my mother generations guided me,

My embryo has never been torpid, nothing could overlay it.

For it the nebula cohered to an orb,

The long slow strata piled to rest it on,

Vast vegetables gave it sustenance,

Monstrous sauroids transported it in their mouths and deposited it with care."

(Leaves of Grass)

When trying to make sense of how, in Finnegans Wake, the inner experience of a dreaming Irish publican could be so expansive and all-encompassing, it is this type of poetic perspective of Whitman's concerning the hidden histories reflected inside of every living soul which might begin to explain things.

"List close my scholars dear,

Doctrines, politics and civilization exurge from you,

Sculpture and monuments and any thing inscribed anywhere are tallied in you,

The gist of histories and statistics as far back as the records

reach is in you this hour, and myths and tales the same,

If you were not breathing and walking here, where would they all be?

The most renown’d poems would be ashes, orations and plays would be vacuums."

(Leaves of Grass)

******

There are not many people who've ever lived about whom it could be said they were ascribed the quality of cosmic consciousness, especially not modern figures, but among those few are Walt Whitman and James Joyce. Richard Maurice Bucke, who wrote the book Cosmic Consciousness in 1901, was a personal friend of Whitman, was Whitman's first biographer, and a big part of his inspiration to write a study of people throughout history who seemed to be suffused with a cosmic consciousness was because of his experiences hanging out with Whitman who he perceived as some kind of demigod. A vast, limitless cosmic perspective is evident across Leaves of Grass, where the poet wrote, "The clock indicates the moment--but what does eternity indicate? We have thus far exhausted trillions of winters and summers, There are trillions ahead, and trillions ahead of them." & "A few quadrillions of eras, a few octillions of cubic leagues, do not hazard the span or make it impatient, They are but parts, any thing is but a part."

As unscientific as all this might be (and come on, we're talking about the minds of poets here), the same level of cosmic consciousness has been ascribed to Joyce---in Philip K. Dick's novel The Divine Invasion (1981) he wrote, "I'm going to prove that Finnegans Wake is an information pool based on computer memory systems that didn't exist until centuries after James Joyce's era; that Joyce was plugged into a cosmic consciousness from which he derived the inspiration for his entire corpus of work." (underline added)

I want to add to this that reading these two works together, Whitman (in Leaves) and Joyce (in the Wake) could be said to have possessed what I will call an "earth consciousness" as well. One of the great sections of Leaves of Grass is entitled "A Song of the Rolling Earth" wherein Whitman celebrates the miraculous mysterious globe that is our only home, this rolling round orb of earth.

"I swear there is no greatness or power that does not emulate those of the earth,

There can be no theory of any account unless it corroborate the theory of the earth,

No politics, song, religion, behavior, or what not, is of account, unless it compare with the amplitude of the earth,

Unless it face the exactness, vitality, impartiality, rectitude of the earth."

The last thing Joyce wrote before he began Finnegans Wake was the end of Ulysses, the Penelope episode, and when describing his approach to that chapter, he told a friend, "It turns like the huge earth ball slowly surely and evenly round and round spinning..." and to his patron he explained, "In conception and technique I tried to depict the earth which is prehuman and presumably posthuman." (see Selected Letters p. 285, 289)

*****

In his very good book The Gift: How the Creative Spirit Transforms the World (2007), the author Lewis Hyde has a chapter on Walt Whitman where he offers an interesting theory on the origins of Leaves of Grass. Sometime in 1855, Whitman came across a huge exhibit in New York City that featured etchings of Egyptian hieroglyphs and tomb carvings that had been assembled by an Italian archeologist 15 years prior, including an etching of the resurrection of the dead god Osiris showing a figure pouring a libation onto Osiris' coffin and long stalks of wheat growing out. This was right around the time Whitman wrote the first edition of Leaves of Grass and also when he published the poem “A Poem of Wonder at The Resurrection of The Wheat” which was included in the final 1892 edition of Leaves of Grass under the title "This Compost."

This directly relates to Finnegans Wake where the Egyptian myths of the resurrection of the dead god Osiris are a recurrent motif in the text, and this image of wheat growing out of the casket of Osiris is alluded to several times, as in "the cropse of our seedfather" (FW 55.08) and "your hair grows wheater beside the Liffey that's in Heaven!" (FW 26.08) There may not be a more important theme in the Wake than that of renewal/resurrection which is evident in the title Finnegans Wake, taken from an Irish American ballad about a corpse who wakes up at his own funeral (notably, after a libation splashes on him).

The renewal/resurrection theme is also extremely prominent in Leaves of Grass, a book that constantly confronts death---"And as to you Death, and you bitter hug of mortality, it is idle to try to alarm me"---while highlighting the resilient forces of vegetation growing out of decay, "It grows such sweet things out of such corruptions." In the aforementioned book The Gift, while discussing the inspiration Whitman took from the Osiris etching, Lewis Hyde emphasizes that Whitman's image of the grass was originally conceived as "the grass of graves" a metaphor which is explored variously throughout Leaves of Grass, as for instance in picturing grass as "the beautiful uncut hair of graves."

We can tie this directly to the Wake when considering some of the ways grass appears in Joyce's text, for instance: on pg 24 we are in the middle of Finnegan's funeral and there's an emphasis on the resurrection, the reawakening, the phoenix bird rising from the ashes, the idea that Finnegan can be rejuvenated in a number of ways including, "And would again could whispring grassies wake him and may again when the fiery bird disembers." (FW 24.11) The "whispring grassies" comes up later in the closing lines of the book (FW 628.12) "We pass through grass behush the bush. Whish!" With that image in mind now notice the whispering effect in this bit from Leaves of Grass:

"And as to you Life I reckon you are the leavings of many deaths,

(No doubt I have died myself ten thousand times before.)

I hear you whispering there O stars of heaven,

O suns—O grass of graves—O perpetual transfers and promotions,

If you do not say any thing how can I say any thing?"

(Leaves of Grass)

As I mentioned above, Lewis Hyde argues that the poem which appears under the title "This Compost" in Leaves of Grass is foundational to Whitman's whole project. "Behold this compost! behold it well!" Whitman declares. He marvels at how the earth can receive the most diseased corpses and somehow cleanse and transform all that death and disease into sprouting spears of green grass, that the earth "gives such divine materials to men, and accepts such leavings from them at last." In Finnegans Wake, this process is embodied in the midden-heap, a giant garbage mound containing all the scattered detritus of history, the "Compost liffe in Dufblin" (FW 447.23). Once you start to draw these parallels, they spring up everywhere you look in these two texts. Not much can be said to be clear about Finnegans Wake, but when read alongside Whitman's Leaves of Grass, clearly there is an important link there. By reading the Wake through an interpretation of Whitman we might begin to gain a better appreciation for the gifts these artists gave to us.

{}{}{}{}{}{}{}{}

- Peter Quadrino