|

| Lucia Joyce and her father in 1924 |

He gave me details about the mental disorder from which his daughter suffered, recounted a painful episode without pathos, in that sober and reserved manner he maintained even in moments of the most intimate sorrow. After a long silence, in a deep, low voice, beyond hope, his hand on a page of his manuscript: "Sometimes I tell myself that when I leave this dark night, she too will be cured."

- Jacques Mercanton (from Portraits of the Artist in Exile, ed. Willard Potts)

Over at his fantastic blog

"Swerve of Shore to Bend of Bay", notable

Finnegans Wake enthusiast Peter Chrisp recently wrote about his experience witnessing the new play entitled "Lucia's Chapters of Coming Forth by Day" which attempts to give voice to the dead daughter of James Joyce who spent the last 47 years of her life incarcerated in a mental institution.

The play has not received

great reviews due mainly to its production values, but the story is definitely an intriguing one. Written and directed by Sharon Fogarty, the play draws heavily upon

Finnegans Wake which, among its many guises, is a modern version of

The Egyptian Book of the Dead, the ancient guidebook to the afterlife that was literally entitled "Chapters of Coming Forth by Day." From Peter Chrisp's

review:

The play places Lucia in the afterlife, with her own personal Book of the Dead. But she's also metaphorically dead because she's spent almost fifty years in mental institutions. There's a strong sense of entrapment. She's unable to escape from the institution and from the shadow of her famous father, James Joyce (Paul Kandel), who appears for most of the play in silhouette behind a screen. The men she falls in love with, such as Samuel Beckett, are more interested in her father than in her. She is frustrated in love and in her attempts to express herself as an artist.

The story of Lucia Joyce has become an increasingly popular one of late with this new play following up a well-received graphic novel

Dotter of Her Father's Eyes written by Mary Talbot who draws parallels between her upbringing as the daughter of Joyce scholar James S. Atherton (author of

The Books at the Wake) and that of Lucia suffering from the neglect of her busy father. The renewed interest in the life of James Joyce's artistically gifted but ostensibly mentally ill daughter would seem to have been sparked by the 2003 biography written by Carol Loeb Shloss,

Lucia Joyce: To Dance in the Wake.

The Lucia biography elicited some in-depth responses at the time, most notably

a lengthy New Yorker piece entitled "A Fire in the Brain" which echoed the response most critics and scholars had to the book: the author made lots of stuff up.

A cursory perusal of the Lucia bio does indeed confirm this opinion. Shloss frequently drums up far more material about Lucia's inner life and her relationship with her father than one could expect a biographer to be aware of considering Joyce's cantankerous grandson Stephen

destroyed most of her letters years ago. Despite this significant gap in source material, Shloss manages to assemble a nearly 500-page book on Joyce's daughter using lots of imaginative embellishment.

The two main points of her book, both controversial, are that the artistic modern dancer Lucia was a major inspiration for the

Wake's style and that, once she became ill, Lucia was essentially sacrificed so that Joyce could finish the book. Here's the

New Yorker piece elaborating on the latter:

Carol Shloss believes that Lucia’s case was cruelly mishandled. When Lucia fell ill, she at last captured her father’s sustained attention. He grieved over her incessantly. At the same time, he was in the middle of writing Finnegans Wake, and there were people around him—friends, patrons, assistants, on whom, since he was going blind, he was very dependent—who believed that the future of Western literature depended on his ability to finish this book. But he was not finishing it, because he was too busy worrying about Lucia. He was desperate to keep her at home. His friends—and also Nora, who bore the burden of caring for Lucia when she was at home, and who was the primary target of her fury—insisted that she be institutionalized. The entourage finally prevailed, and Joyce completed Finnegans Wake. In Shloss’s view, Lucia was the price paid for a book.

It's a tragic story that makes for good theater, but whether Lucia could have been "saved" by her father had he not been so caught up in finishing his giant puzzle book is unlikely. For years, Joyce was ignoring the advice of family, friends, and doctors by investing excessive amounts of time and money trying to find a cure for her illness. He tried everything from sending her to see Carl Jung (who told Joyce he and his daughter are in the same river but he is swimming while she's drowning) to a whole array of alternative cures (like saltwater injections) with no real progress, yet he refused to give up on her. He was convinced she possessed the same spark of genius that he had, that she wasn't insane but gifted, even clairvoyant.

I'm partial to the diagnosis Jacques Lacan retroactively applied to the situation which was that Joyce and his daughter were both suffering from a psychosis, but while the father had his writing to channel all of his unconscious energy into---thus balancing out his psychotic symptoms through an affect Lacan calls

"le sinthome"---the similarly gifted, artistically inclined daughter failed to find a sustained artform to devote herself to.

Lucia got into modern dance during the 1920s and clearly had a talent for it. She toured with a dancing group called Les Six de Rythme et Couleur (Joyce's dancing rainbow girls in

Finnegans Wake bear traces of this outfit), studied at various schools in Paris, and in what would be perhaps the shining moment of her life, was a finalist in an international dance competition in 1929. While she didn't win the competition, she was the crowd favorite, the rowdy audience booed and heckled when she didn't win and chanted to the judges (in French) "The Irish girl! Gentlemen, be fair!" For her performance she wore an evocative shimmery fish costume which she'd made herself, pictured below.

During this period she was profiled in the

Paris Times:

"Lucia Joyce is her father's daughter. She has James Joyce's enthusiasm, energy, and a not-yet-determined amount of his genius... When she reaches her full capacity for rhythmic dancing, James Joyce may yet be known as his daughter's father."

Her dancing career sputtered though, when she made the poor decision to fortify her dancing foundation by going back to school to study ballet. Already in her late 20s, she was too old to begin such a rigorous practice from scratch and quickly flamed out. Shloss speculates that her mother Nora, a lifelong adversary, pushed her to quit dancing.

The failure of her dance career combined with a string of failed romantic relationships likely hastened Lucia's descent into mental illness. At one point, she had fallen in love with her father's young amanuensis and protégé Samuel Beckett only to be told bluntly that he was only interested in her father. According to Richard Ellmann, Beckett later told a friend "that he was dead and had no feelings that were human; hence had not been able to fall in love with Lucia." Revealingly, after Beckett died a photo of Lucia in her dancing fish outfit was found at his desk. He'd kept it for more than 60 years.

* * *

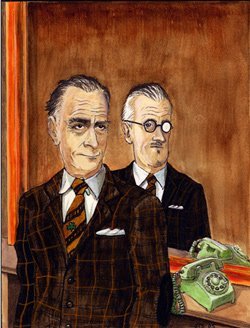

|

| Artist Roy Wallace depicts James Joyce, Samuel Beckett, and Lucia. |

As for the influence Lucia had on

Finnegans Wake, while it may not have happened the way Shloss portrays it in her book, Lucia surely plays a major role in Joyce's magnum opus. Building off the scene a cousin of the Joyce's witnessed at their house once, Shloss paints this picture:

There are two artists in this room, and both of them are working. Joyce is watching and learning. The two communicate with a secret, unarticulated voice. The writing of the pen, the writing of the body become a dialogue of artists, performing and counterperforming, the pen, the limbs writing away.

The father notices the dance’s autonomous eloquence. He understands the body to be the hieroglyphic of a mysterious writing, the dancer’s steps to be an alphabet of the inexpressible. . . . The place where she meets her father is not in consciousness but in some more primitive place before consciousness. They understand each other, for they speak the same language, a language not yet arrived into words and concepts but a language nevertheless, founded on the communicative body. In the room are flows, intensities.

You'll notice Shloss injecting a great deal of her own creative interpretation into things. This is what she does throughout the book and it's why she hasn't been taken too seriously.

She employs this brand of creative interpretation to the material from the

Wake, as well, frequently reading into it references to Lucia. For this I don't think she can be faulted, though, as this type of projection of one's own theories when deciphering the text is exactly how it

should be read. And in her reading of Joyce's twisted "nat language" (FW p. 83) she often presents a fairly good case for there being present allusions to Lucia.

The Nuvoletta scene of the

Wake, which is prominently featured in the "Lucia's Chapters of Coming Forth by Day" performance, carries strong echoes of Lucia, the character's name even morphing into "Nuvoluccia" (FW p. 157) at one point. The book's "daughter of pearl" (FW p. 399) Issy and her accompanying rainbow girls have always been the most difficult of the main characters to pin down, there's certainly some of Lucia embedded in there.

Lucia Anna Joyce was the apple of her father's half-blind eye. The two had a special relationship, one might say they were on the same wavelength. As one of Lucia's fellow dancers, Helene Vanel, put it: "Yes, she was really the spiritual daughter of James Joyce; she was his extension. She was the single element on earth that prolonged his existence, both inside and outside of his work."

After she was entered into a mental institution, Joyce continued to rally in defense of his daughter, writing to Harriet Shaw Weaver, "I am again in a minority of one in my opinion as everybody else apparently thinks she is crazy. She behaves like a fool very often but her mind is as clear and unsparing as the lightning" and wrote to a friend about "the lightning-lit revery of her clairvoyance." (There's lightning flashing outside my window as I write this.) In an essay for the

James Joyce Quarterly entitled "Lightning Becomes Electra: Violence, Inspiration, and Lucia Joyce in

Finnegans Wake," Joyce scholar Finn Fordham points out that in the late 1930s there were several additions made to the text linking together Lucia and lightning (Lucia in Italian means light). It's also revealing that, as Shloss notes, when

Finnegans Wake was about to be published Joyce wanted to show Lucia the first copy.

Like most everything in

Finnegans Wake, we likely won't ever get a straight answer about the role Lucia played in its creation. Her mystery grows darker and invites further speculation since her letters were destroyed. What was Stephen Joyce trying to hide? Another denunciation aimed at Shloss' book stems from her speculation that there was some sort of sexual indiscretion involved in Lucia's early life, likely involving her brother---Stephen's father---that contributed to her condition (though she admits there's actually no evidence for this). At the heart of

Finnegans Wake is a vague nightmarish guilt for some sexual act committed by the main character. Whatever may have actually occurred is purposely obscured, the story twisted, tangled, and distorted through degrees of gossip.

The reader is never able to get to the heart of the matter, always picking up clues and hints while the truth recedes further, teasing and laughing off into the darkness. The curious persist, sensing something major just beyond their grasp. Confined to a mental institution until her death in 1982 (the centenary of her father's birth) and forever silenced by a paranoid family member afterward, we'll likely never know the full story of Lucia Joyce. I don't think it's crazy to suggest there are encoded secrets about Joyce's beloved daughter buried within the pages of his puzzle book, never to be solved.