I was on an extended stay in Dublin a few years ago and found myself in a shared space somewhere out in Leopardstown on the outskirts of the city. The Leopardstown horse racing course is mentioned multiple times in Finnegans Wake and is still active to this day. No leopards are found in the area, though, the name was a modification of Leperstown, as it used to be called, because that's where the city had once quarantined its leprous citizens. In the Wake it appears as "Leperstower" (FW 237) and "Leperstown" (FW 462). It comes up in a classroom scene in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man when a student is missing during roll call and someone blurts out, "Try Leopardstown!"

No matter where I went, whether all the way out in Leopardstown or in the heart of the city, every time I looked up something nearby it seemed there was mention of it in the Wake. It's hard to overstate how much one feels embedded in the Wake due to the places and place names one encounters in that city. At one point I relocated to the city center and, looking on the map, I notice across the street from my hotel was a funeral parlor by the name of Fanagan. This was on Aungier Street, central Dublin. Sounded familiar, so I looked for it in Finnegans Wake and, sure enough, Fanagan's funeral parlor is punned on several times in the book. They've been in business in the same location since the year 1819. You will find "Fanagan's weak yat his still's going strang" (FW 276.22) among other appearances, "and all the fun I had in that fanagan's week." (FW 351) That's Dublin, the center of Wake world. The text of Joyce's encyclopedic 1939 novel is so wide open it seems to encompass everything that's ever been or will be, yet it all revolves around the reliable center anchor that is Dublin and environs. A real place on a map. The same Dublin I was staying in, strolling through, the same street as present-day Fanagan's undertakers fashioning their own wakes for Finnegans for the last two hundred years.

Being in Dublin means being at a crossroads of mulitverses, a centerpoint of alternate realities, the axis of a mandala where worlds intersect and converge. Joyce scholar Struther B. Purdy wrote an article for the JJQ entitled, "Is There a Multiverse in Finnegans Wake, and Does That Make It a Religious Book?" In that piece, Purdy argued that Joyce's linguistic manipulations and the unmooring of space/time leads to words creating alternate worlds:

Past and present are coterminous because they are different places. Different places and different times coexist; words make worlds. Worlds are therefore a) plural and b) as unlimited in number as are words. "Budlim" (FW 337.26) is not Dublin distorted phonologically to add to the description of the earth's Dublin but a Dublin-like city in another Ireland, possibly the eerieland/"Ereland" of FW 264.31. The "battle of the Boyne" is locatable as the battle of that name in 1690, while the "bettlle of the bawll" is a shadow battle in a different world. (FW 114.36, 337.34).

Further multiplying the shadow worlds of "Dublin-like" cities in Joyce's "Errorland" (FW 62) or "Aaarlund" (FW69) hovering next to and intersecting with earth's Dublin are the various names for Dublin that proliferate throughout Finnegans Wake. Wander the city, take the bus, or ride the train around Dublin, and you'll frequently encounter the Irish names for places (signs and announcements include both the English and Irish language) especially Baile Atha Cliath, the city's Irish name, which translates to Town of the Ford of Hurdles. Hurdles are basketwork, (hence "at Wickerworks" FW 289) which was used as a ford or bridge to cross the river. In the Wake it appears as "fordofhurdlestown" (203.07). Seeing the words Baile Atha Cliath pop up so often around town always harkens back to the Wake where variations of "Baulacleeva" (FW 134) and "Bauliaughacleeagh" (FW 310) inundate the page, "the deep drowner Athacleeath." (FW 539). In the Dublin of the pre-Viking invasions era, there actually were two settlements along the Liffey named Atha Cliath (hurdle ford) and Dubh Linn (black pool). The two names are now interchangeable. Dear dirty Dublin or "Dix Dearthy Dungbin" (FW 370) the center of the Joycean universe, it is astounding when you consider how devotedly Joyce's books focus on Dublin.

* * *

All of Joyce's major published works focus on Dublin and when I was there I was wondering, why did this talented author devote all of his energies to document this place, its neighborhoods and characters and histories? And why did he stay away from Ireland for so long? And, especially, exactly when was it that Joyce had last set foot on the streets of Dublin?

Even after his young and defiant departure from the emerald isle with Nora Barnacle in 1904, Joyce made a few trips back to Ireland, first in 1909 and again in 1912. Never again after that. Biographers note that he stayed away for fear he might be attacked in the street, thinking of an incident that happened to Parnell where an assailant threw quicklime powder in his eyes. Nora and the kids got caught in a crossfire in Galway on a visit once. The period of the Irish Revolution was extremely violent, and nationalists not only might accuse Joyce of not sufficiently supporting their cause, in those days they were likely to be angered by Joyce's depictions of the Irish.

Whether reading Joyce's books or walking the streets of Dublin, the emphasis on psychogeographies leads me to be interested in recalling the facts of when was the last time Joyce was physically present in the country he wrote so much about. Here are some details on the last visits James Joyce made to Ireland:

- July 1909 the exile returns to Dublin for the first time since he left with Nora in 1904. Joyce arrived by ship into Kingstown Pier (now Dun Laoghaire, same pier from which they had disembarked). First thing he spotted on getting off the ship was Oliver Gogarty's fat back, and he avoided his old nemesis. James and his son Giorgio took the train into the city center and were welcomed by his father and sisters at Westland Row Station (present day Pearse station). This was the trip when Joyce bumped into a friend, Cosgrove, who said he'd taken long walks with Nora after dark when they were first dating. Joyce fell into despair, went over to 7 Eccles Street (in north Dublin) to be consoled by his friend Byrne. These events became integral to Joyce's conception of his novel, Ulysses. On that same trip, Joyce met with his nemesis Gogarty for one final tense encounter. Gogarty would soon be transformed by Joyce's pen into Buck Mulligan, the arrogant foil to Stephen Dedalus in Ulysses. By the time Joyce left Dublin with his son in September 1909, he felt sick of the place.

- But he would return shortly thereafter, on 21 October 1909. This time he stayed for more than two months. This time it was a very awkward departure when he left Nora in Trieste. He was heading into Dublin for a business venture, looking to find a good location for the new cinema he was helping to put together, the first of its kind in Ireland. He settled on 45 Mary Street, not far from busy Sackville Street (present day O'Connell Street). On this trip, he was also meeting with publisher George Roberts trying to get his first book Dubliners published. During this trip he "went to Finn's Hotel, visited Nora's old bedroom and wept. After dining there, he sat at the table and wrote to her, sobbing as he did so." (Bowker, p. 189) Joyce and his business partners went up to Belfast looking for more sites to build a cinema. The Volta was opened on Mary Street in Dublin in December. During this long time away from his young wife, Joyce and Nora exchanged naughty letters. Seems he had become so aroused, he couldn't resist going to visit the brothels in Nighttown. There's an implication that he might've caught a venereal disease at this point. He confessed this to Nora who stopped sending letters to him for a while after.

- July 1912, Joyce rushed off to Dublin with Giorgio to meet Nora and Lucia. Bowker pg. 200-201 details how Nora brought Lucia to Ireland to meet her family in Galway in 1912. They also went east where the Dublin Joyces met the girls at Westland Row station on July 8. That's when John Joyce broke down in tears at the sight of Lucia, feeling sad that he'd become disconnected from his favorite son. James Joyce in Trieste was troubled with jealousy, grew anxious over not hearing from Nora, became sad because she stayed at Finn's Hotel without even mentioning to him that it was where they first met. So he borrowed money from friends and rushed off to Dublin from Italy with Giorgio on July 12. Upon arrival, they stayed at 17 Richmond Place with his brother Charlie and family. Of this visit, Bowker writes:

Joyce was anxious to refresh his memory of the city which he had made the centre-point of his creative imagination. There were places to revisit and fragments of gossip to be gleaned from every encounter, every visit to a bar, every edition of a Dublin newspaper. (p. 201)

After more difficulties with the printers and publishers over the publishing of Dubliners, Joyce wrote the broadside "Gas from a Burner" attacking those who refused to publish his works for fear of upsetting the Ireland of the time under British rule and Catholic control. He took a ship back to Trieste, never to return to Ireland again. Soon thereafter he started writing Ulysses.

Decades later, in 1941 when Joyce and his family managed to escape Nazi-occupied France to enter into Switzerland, an Irishman named Sean Lester greeted them. Lester, the last Secretary-General of the League of Nations, records Joyce's answer when Lester asked him why he did not go home to Ireland: "I am attached to it daily and nightly like an umbilical cord."

(see more here)

* * *

|

| "And Dub dig glow that night" FW 329.14 |

The city today has a population that keeps growing, worsening a severe housing shortage. Dublin has become an international tech hub, home to headquarters of Google, Facebook, Microsoft, Verizon, &c. The many colorful lights gleam at night from ultra-modern architecture along the quays of the “efferfreshpainted livy” (FW 452), the effervescent ever-fresh-painted Liffey. Modernized as it has become, the city still constantly summons connections to Joyce's 1939 novel. Of course, the same applies for Ulysses, that book by itself generates substantial tourism to Dublin. As I mentioned in a previous post, I got to walk around the city during the Ulysses centennial on Bloomsday 2022 and really get a feel for the local pride around that book (John McCourt's recent book Consuming Joyce: 100 Years of Ulysses in Ireland gives a great account of the shift in Ireland's attitude toward Joyce).

I'm taking you through some of my experiences exploring sites relevant to Joyce's work, especially Finnegans Wake. I had been reading the book for at least a decade before I ever set foot in Dublin. When you gain even a passing familiarity with districts in Dublin, a shockingly significant portion of the text starts to become recognizable. I think it is likely true that nothing could better prepare someone to read Finnegans Wake than to visit Dublin and learn about the city. I don't mean to promote the place, although I do love it there. It's just that the Wake is obsessed with Dublin to the point of absurdity, at one point when the opaque book offers a moment of clarity, for instance, it turns into a commercial promoting the city:

This seat of our city it is of all sides pleasant, comfortable and wholesome. If you would traverse hills, they are not far off. If champain land, it lieth of all parts. If you be delited with fresh water, the famous river, called of Ptolemy the Libnia Labia, runneth fast by. If you will take the view of the sea, it is at hand. Give heed! (FW 540.03-08)

I think it is fair to say the text of the Wake contains even more information about Dublin than Ulysses does. Dublin serves as the setting for Ulysses and it is as thoroughly described as could be. In the Wake, though, Dublin becomes the entire texture of the language. Dublin is the subject, object and predicate. City district names blend, morph, and become verbs. To the extent there are characters in the Wake they are on some level representative of aspects of the environment, the father connected with Howth Head, the mother is the River Liffey, the daughter is a cloud, for example.

(clouds over Dublin)

Everything in the entire history of this place across varying scales of time all coexists on the same plane in the Wake. Dublin becomes a crossroads of multiverses where time folds into and becomes part of space. You notice there is so much history embedded everywhere around Dublin, and how the text of the Wake seems to embody this landscape, its earth layers filled with centuries of history. There is a Timefulness to the place. This is a term coined by the geologist Marcia Bjornerud to describe spaces containing a palpable presence of deep history. As she explains: "I see that the events of the past are still present… This impression is a glimpse not of timelessness but timefulness, an acute consciousness of how the world is made by–indeed made of–time." (p. 127 Saving Time, Jenny Odell) I thought of this when I saw a Martello Tower or when I saw Howth Castle or the rocky cliffs in Dalkey or the promontory in Bray or the rugged coastline at Greystones. Joyce in the Wake captures the essence of this observation in the phrase "this timecoloured place" (FW 29.20).

A more expansive example of this timefulness quality of Dublin is provided by Joyce when Stephen is walking along Sandymount Strand in the "Proteus" episode of Ulysses and he has this vision of being among the vikings:

Galleys of the Lochlanns ran here to beach, in quest of prey, their bloodbeaked prows riding low on a molten pewter surf. Dane vikings, torcs of tomahawks aglitter on their breasts when Malachi wore the collar of gold. A school of turlehide whales stranded in hot noon, spouting, hobbling in the shallows. Then from the starving cagework city a horde of jerkined dwarfs, my people, with flayers’ knives, running, scaling, hacking in green blubbery whalemeat. Famine, plague and slaughters. Their blood is in me, their lusts my waves. I moved among them on the frozen Liffey, that I, a changeling, among the spluttering resin fires. I spoke to no-one: none to me.

"Famine, plague, and slaughters" marked the years of the brutal Viking invasions of Dublin. What Stephen describes are not only scenes of bloody wars in Scandinavian Dublin but also visions of hordes of locals feeding off beached whale carcasses "hacking in green blubbery whalemeat," and this cluster of images comes up again in the first chapter of the Wake as the reader is guided along on a tour of Dublin.

Men like to ants or emmets wondern upon a groot hwide Whallfisk which lay in a Runnel. Blubby wares upat Ublanium. (FW 13)

Men feeding off "a groot hwide Whallfisk" whale laying in a runnel or a river channel. And the last part is not just the blubber wares of whale meat but the bloody wars at Eblana, another name Joyce uses for Dublin. (Eblana was the name given by Ptolemy in early maps of the Dublin area.) The bloody wars in Dublin becomes a motif repeated again a few more times in the ensuing paragraphs, while also giving the various names for Dublin.

Blubby wares upat Ublanium.

…

Blurry works at Hurdlesford.

…

Bloody wars in Ballyaughacleeaghbally.

…

Blotty words for Dublin.

(FW 13-14)

I think what is being captured in the varying names for Dublin being stacked this way is showing the changes across time due to the bloody wars and blurry works. But, again, in the Wake all of these historical eras and events are ongoing and coterminous with each other, all active in the same space.

In the last post, I was describing visions of Dublin, seeing the ink and paper of Finnegans Wake merging with the sewage, rainwaters, roots and soil of the city. I was thinking of the letter in the book, on one level representing the Wake itself, buried deep under the city, taking root in the inner terrain of Dublin. Interlocking with the city innards, like an artery, soaking in the detritus of the city, draining down to the Liffey. Blackpool. Dubh Linn.

what was beforeaboots a land of nods, inspite of all the bloot, all the braim, all the brawn, all the brile, that was shod, that were shat, that was shuk all the while, for our massangrey if mosshungry people, the at Wickerworks, still hold ford to their healing (FW pg 288)

* * *

If to be able to read Ulysses it is advisable to relate the movements of the characters to a map of Dublin… in Finnegans Wake it is the text itself that, in a sustained embodiment of modern creativity, becomes the map, the pilot's book, the topographical pattern, the metaphoric grid, the model and the structure capable of projecting the image of the world onto a screen, on a two-dimensional page…

(Carla Vaglio Marengo, "Mapping the Unknown, Charting the Immarginable, Fathoming the Void: Space, Exploration and Cartography in Finnegans Wake", from Joyce Studies in Italy, 2022)

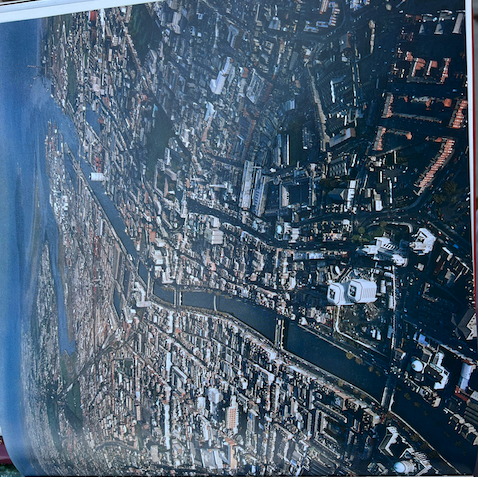

There is a circularity to the geography of Dublin as it's presented in the Wake. It starts with a sentence that cycles around town starting from Adam and Eve's Church, going along the swerve of shore, out to Vico Road in Dalkey, and then "by a commodious vicus of recirculation" cycling around out to Howth Castle. The drilling down into the history embedded in the layers of the landscape I mentioned above seems like a centripetal spiralling down into the vertical depths of "Shuvlin, Old Hoeland." (FW 359.24-26) The "Nightlessons" chapter (II.2) has a bunch of geographical aspects to it, the lessons studied by the children involve the geography of Dublin. It seems the Euclidean overlapping circles diagram on FW p. 293 has a geographical interpretation to it, maybe that is what the directions are providing in the second paragraph of that chapter (on pg 260), where the reader is given an itinerary through the city, we circle "wheel, to where. Long Livius Lane, mid Mezzofanti Mall, diagonising Lavatery Square, up Tycho Brache Crescent" (FW 260) and so on.

A few pages prior there is a passage with a geographical survey of the city: "where G.P.O. is zentrum and D.U.T.C. are radients write down by the frequency of the scores and crores of your refractions the valuations in the pice of dingyings on N.C.R. and S.C.R." (FW 256.29-32) This denotes the GPO, or General Post Office, on O'Connell Street as the center ("zentrum") of the city, with radii "radients" branching out via the DUTC (Dublin United Tram Company) pathways, and then the "N.C.R." and "S.C.R." are the North Circular Road and South Circular Road. When you stare at the map of Dublin with this in mind, looking at the rounded roads along the north and south you could see how the city might be considered a circular or oval oblong shape, as Joyce calls the city elsewhere in the Wake, "D'Oblong." (FW 266.06) This spatial geomapping has some historical accuracy, as described in Roy Benjamin's book Beating the Bounds (2023), the North and South Circular Roads were originally designed to be the boundaries of the city.

Just as the historical events of the place are not abstract or in the past but actively occurring alongside each other, the city of Dublin doesn't just exist as a static entity in the Wake, it's constantly in motion taking formation as the streets branch out from the river in the heart of the city forming like veins carrying the lifeblood of the community. When Joyce had sent his patron Harriet Weaver a draft section of the Anna Livia chapter including his annotations shedding light on what was going on in the passage, he explained one of the lines this way: "All this is to give the idea of the growth of Dublin, branching out into one street after another." The branching streets and the tracks of the trams and trains venture out from the heart of the city to the suburbs and back. This is the same network described at the opening of the "Aeolus" chapter of Ulysses with the headline blaring "In the Heart of the Hibernian Metropolis" followed by details of the same radii lines of the Dublin United Tram Company expanding outward from the GPO in the center of the city.

The detailed geomapping with the GPO serving as the centerpoint becomes even more outlandish elsewhere in II.2 when the focus is on the suburb of Chapelizod, to the west of city center, the place where the Mullingar Inn pub is located. This pub is considered to be the location of all the events of Finnegans Wake, with the pub owner and his family asleep upstairs and, according to some interpretations, dreaming all of what we're reading in the book. In a passage on pg. 265 the distance from the Mullingar pub to the GPO is given as "only two millium two humbered and eighty thausig nine humbered and sixty radiolumin lines to the wustworts of a Finntown's generous poet's office." (FW 265.25-28) Naming the GPO "generous poet's office" is fantastic, bravo Joyce, but breaking down the distance into "radiolumin lines" is truly mindboggling. McHugh's notes say that there are 2,280,960 twelfths of an inch in three miles (the distance between the GPO and the Mullingar pub). But "radiolumin lines" conjures not only the radius, but also rays (radius) of light (lumin) which gets into all kinds of physics ideas about lightspeed as a measurement. Too much for me to comprehend right now, but we will come back to the landmark Mullingar pub later on.

* * *

Centering ourselves at the General Post Office on O'Connell Street, nearby there is the pointed Dublin Spire structure, the city's focal point and a memorial of the site of Nelson's Pillar which once stood there before it was blown up in 1966. If you started from there and walked a few blocks up to Henry Street and turn left, walk a bit and you'll be on Mary Street, a busy shopping area, and you will pass by 45 Mary Street which was the site of the Volta Theater, the first cinema in Dublin, which Joyce had helped arrange on one of his final visits to Ireland.

From there if you turn left and walk back down toward the river you'll come upon Bachelor's Walk along the north quay of the Liffey—this street is mentioned on pg 214 of the Wake, a part you can listen to Joyce himself reading aloud in a recording, "of a manzinahurries off Bachelor's Walk." From Bachelor's Walk you can cross onto Ha'Penny Bridge to walk across the Liffey onto the south side of the river. This bridge was originally called "Wellington's Iron Bridge" and it appears this way on FW 286.11, with the capitalization and no distortions. On one of my stays in Dublin I was in lodgings right on Bachelor's Walk and got to walk across Wellington's Iron Bridge every day. Here's the view from the bridge after crossing to the southside, where you can see Merchant's Arch, a spot featured in Ulysses.

|

| Merchant's Arch from Wellington's Iron Bridge (aka Hapenny Bridge) |

Once you cross the bridge you can walk thru the archway, this area used to be filled with bookshops, described in the scene where Bloom is observed scanning books in Ulysses: "They went up the steps and under Merchants’ arch. A darkbacked figure scanned books on the hawker’s cart." Walk under the archway, go a few blocks then turn left and you'll be heading toward Trinity College. In June 2022, I had the honor of presenting a paper in an auditorium at Trinity for the centennial Joyce conference. It was an incredible moment in my life. I spoke on the morning of Bloomsday. Just outside of Trinity if you walk down Nassau Street you will encounter Finn's Hotel, the site where James and Nora Joyce first met. Finn's Hotel is considered by some scholars to be Joyce's original title for Finnegans Wake. Walk around the corner and you'll find Sweny's Pharmacy and down the street from there is present-day Pearse train station, which used to be Westland Row station which comes up in Ulysses and which Joyce himself had arrived at in one of his last visits to Dublin.

When walking down Nassau Street you can also turn right and go down Dawson Street, and there you will find the historic Hodges Figgis bookstore. This place has been in operation for over 200 years (albeit including moving locations), it is one of the oldest bookshops in the world. It pops up in Ulysses and in Finnegans Wake. It's a fantastic bookstore, a great place to browse for hours. I can tell you that they've got an impressively deep collection of Joyce books. I was there eyeing their several shelves of Joyceana and, can you imagine what it must've felt like when I discovered they had a book on the shelf which named me in the index? I'm not kidding. The book is called James Joyce and the Arts (part of the European Joyce Studies series) and there's an essay in there by Derek Pyle which mentioned THIS BLOG in a footnote. I was in the heart of Dublin, in a bookstore that appears in Ulysses and the Wake, and found my name in a footnote in a Joyce book. Achievement unlocked, life goal accomplished.

* * *

The inspiration for the thoughts I'm sharing here I originally conceived while standing atop Killiney Hill observing the landscape around Dublin, the rolling green Wicklow Mountains in the distance, and I was envisioning how the hills would look in the night in centuries past when, in the words of the Wake, "There were fires on every bald hill in holy Ireland that night" (FW 501). I've been curious about that phrase "holy Ireland" and it doesn't seem to be common, then I saw the same phrase used in a book by the American poet Susan Howe, The Quarry, which mentions "reciting secret languages of holy Ireland." Susan Howe is the daughter of Mary Manning Howe, an author and playwright who was born and raised in Dublin. She was a close friend of Samuel Beckett, and as a playwright she adapted Finnegans Wake to the stage. (see here)

Ireland is a famously evocative environment for writers. I'm focused on Joyce and the Wake here, but Ireland has a rich literary tradition beyond Joyce, and the country today continues to be very welcoming to writers. There are frequent articles about the literary mecca of Dublin, here's one example.

One of the first things that strikes me every time I arrive in Ireland is noticing the old stone walls covered in mossy mold from the sea air, soon as I see the mossy old stone I know where I am. This comes up in the Wake where "though he's mildewstaned he's mouldystoned" (FW 128.02) That moldy stonework and the sea air are part of the recipe for literary brainwork I associate with "holy Ireland."

A passage in Ulysses captures this mixture beautifully:

The air without is impregnated with raindew moisture, life essence celestial, glistening on Dublin stone there under starshiny coelum [Latin, "sky"]. God’s air, the Allfather’s air, scintillant circumambient cessile air. Breathe it deep into thee.

The aforementioned Susan Howe has a sister who is also a renowned poet, Fanny Howe. In her excellent book The Winter Sun, Fanny Howe writes of when she and her sister, both American born, first went back to their Irish mother's home country and encountered Dublin:

"Then we were herded into a bus and headed for Dublin where the clouds were much lower than they were in America. My sister and I gulped in the atmosphere of a new country; it entered our systems like a potion that suffuses the whole and would never leave either of us. It was our mother's body." (pg 30, The Winter Sun: Notes on a Vocation)

"Holy Ireland." "God's air, the Allfather's air," the atmosphere that was "[their] mother's body." To bring this "back to Howth Castle and Environs", the "scintillant circumambient cessile air" and the mossy stone that make up the poetic potion were noticeable in abundance when I went up to Howth one afternoon. I took the DART, Howth is the northmost stop. Howth feels like how I imagined Ireland would be before I ever visited the country. Howth was very green, chilly, cloudy, soggy wet, misty, lots of boats on the docks, and plenty of old stone structures covered in moss. The vibes feel very historical there. I went and checked out Howth Castle and environs. The piratess prankquean "grace o'malice" had trod this ground, ported at this peninsula. It was so interesting being there observing this real and historical space and considering how deeply it has been lodged into my brain as a mythic site, thanks to the legendary Grace O'Malley scene in the Wake.

Grace O'Malley was a real person, a female pirate from Ireland who, according to legend, arrived at Howth Castle one night in the 16th century, hoping to stay for the night as it was customary in those days for the castle to keep its doors open to offer hospitality to visitors. After she was denied entry at the door, she kidnapped a child from the royal family. All of this is enacted in the language of a fairy tale in the Wake, where the prankquean "grace o'malice" poses riddles to the doorman and kidnaps two children. I found the experience of walking around Howth surreal, considering there's a street named after Grace O'Malley and you can walk up the Howth Castle door where the prankquean "made her wit foreninst the dour." (FW 21.16) Walking around the castle area it felt imbued with a spooky presence, this was a relic of half a millenia ago, the grounds were well trodden, the walls seemed to be alive. Look at the rotting and tree-rooted parapet in the second picture below, notice the timefulness, this was a space filled with time.

|

BACK TO HOWTH CASTLE AND ENVIRONS

|

* * *

In the year 1906, James Joyce was living in Rome, working long hours as a clerk at a bank, finding very little time to write, and he felt miserable. His biographer Gordon Bowker notes: "He wished himself far away–beside the sea at Bray…"

Away from home only a couple years at that point, Joyce longed for the scene of his childhood home by the sea in Bray. Whereas Howth with its rocky promontory is the northernmost stop on the DART train in Dublin, at the opposite end the southernmost stop on the train is in the village of Bray which also has a jutting promontory. Joyce conflates the two places in the Wake, calling it "Brayhowth" (FW 448.18). The train station has a mural of Joyce. I got to spend a few days exploring Bray, a stony beach scene. There's a film studio there, one day as I was walking along the rocky beach I saw a camera crew doing a shoot.

|

| Bray Head |

Joyce spent years as a child living with his family in a house on Martello Terrace in Bray, right next to the sea. I got to see the house where Joyce lived from 1887-1891, it is extremely close to the beach. When the Joyces lived there the house would sometimes flood when the waves got especially rough. Being there and seeing how close it was to the shore, seeing the incredible view facing out from the front of the house, looking straight towards the big rocky green Bray Head, seeing the waves and the sea, I thought OF COURSE a future poet would've grown up here.

The Bowker biography of Joyce notes: "James would sometimes take [his brother] Stannie for walks along the beach. Living and walking beside the sea became a lifelong pleasure for him." (Bowker 28) This beach was also where Joyce acquired his fear of dogs, he and Stannie once threw rocks at a dog on the beach, it attacked them and bit a chunk out of Joyce's chin, supposedly the goatee he maintained as an adult was to hide the scar. This was also the house where the famous scene of the political fight over Parnell at the family Christmas dinner table that's depicted in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man would've taken place.

In 1935, Joyce's daughter Lucia went to stay in Ireland for a summer, and she stayed with some family members in Bray. She thought Bray Head looked like her father's profile (see

Lucia Joyce, Schloss, pg. 343). In one of his letters, Joyce wrote to her suggesting she could take the train into Dublin city center to visit the GPO.

* * *

|

| view from Blackrock |

About midway between Howth and Bray along the coast is the neighborhood of Blackrock. When riding the train seeing the Irish names for the stops I was interested in the Irish name for Blackrock An Charraig Dhubh, because of the Dubh for black, same as Dubh Linn, for black pool. One night I had dinner at the beautiful home of some friends I'd met in a reading group at Sweny's. The view out their front window looking at the bay was picturesque, with Howth Head prominent on the horizon. When Joyce's family moved from the house by the sea in Bray up to a house in Blackrock, living closer to the city center of Dublin transformed the young Joyce's life. His father would take him around the city showing him sights and telling him stories, as Bowker in his Joyce biography explains:

Joyce was absorbing the intricate layout of the city he was to immortalize in literature... landmarks not just on the map of Joyce's Dublin but also on the map of his creative consciousness. And through those streets of that Victorian city, past shops, cafés, bars and newspaper offices, moved and jostled the Dubliners [who] would people his fictions. John sometimes joined in his son's sightseeing perambulations, regaling them with tales of Dublin life and characters and pointing out places of interest... It was a leisurely city with an air of languor, not subject to the dictates of business or industry. The sights, sounds, smells and texture of Dublin introduced James to a world he would transform into the focus and playground of his imagination. The spirit of the place would permeate his thoughts and writing, wherever he happened to be in the world, and would supply the dream-like setting for the great rumbustious Finnegans Wake. (Bowker, p. 42)

There's an interesting mention of Blackrock in

Portrait of the Artist as well, with Joyce once again focused on the geo-mapping of the city:

Outside Blackrock, on the road that led to the mountains, stood a small whitewashed house in the garden of which grew many rosebushes... Both on the outward and on the homeward journey he measured distance by this landmark: and in his imagination he lived through a long train of adventures…

The image above is the view from the train stop at Blackrock. Often the mentions of Blackrock in Finnegans Wake are having to do with the Dalkey-Blackrock-Dunleary tramway, "Dullkey Downlairy and Bleakrooky tramaline" (FW 40.29-30) which I believe would have been essentially the same route as the present day DART train.

In fact, I found that virtually every single one of the present day DART train stations in Dublin are named in FW. Compare the following list (incl. FW page/line numbers) with the map below:

- Howth (too many to list)

- Kilbarrack 315.28; 327.24

- Raheny 17.13; 39.09; 129.24; 142.15; 204.18; 497.20

- Harmonstown (see above, also nearby "Artane" appears twice)

- Killester 427.01

- Clontarf Road (too many to list)

- Connolly (Amiens St) 443.15; 549.31

- Tara Street (too many to list)

- Pearse (Westland Row) 553.3

- Grand Canal Dock several references to streets on Grand Canal

- Sandymount 247.34; 323.02

- Sydney Parade 60.27; 553.31

- Booterstown 132.04; 235.36; 386.24; 390.03; 507.35; 582.33

- Blackrock 40.30; 83.20; 294.22; 541.02; 582.32

- Seapoint 129.24; 588.15; 594.34

- Salthill and Monkstown 261.F04

- Dun Laoghaire (too many to list)

- Sandycove/Glasthule 321.08; 529.23

- Glenageary 529.26

- Dalkey (too many to list)

- Killiney 295.F02; 431.21; 433.13

- Bray 53.30; 313.31; 448.18; 522.30; 537.34; 624.32

* * *

Back toward the city center, I remember walking around the streets I'd often encounter the name Kimmage Outer seen on bus tags in the city. It's another thing recognizable from repeated appearances in the Wake, the name of a district in southwest Dublin, right near where Joyce was born.

There's an odd and obscure pattern to the way Kimmage Outer (K.O.) appears encoded in the Finnegans Wake text, the clatter of noises in the soundwaves of the dreamworld sometimes catches the frequency of radio calls:

pg 13 "Dbln. W. K. O. O. Hear?"

pg 35 "pingping K.O. Sempatrick's Day and the fenian rising"

pg 72 "ring up Kimmage Outer 17.67"

pg 275 "phone number 17:69 if you want to know"

pg 456: "O.K. Oh Kosmos! Ah Ireland! A.I."* * *

To be continued in Phoenix Park ...